Have you ever wanted a fantasy to be real so bad it hurts? Entering Narnia (or Fillory), seeing a unicorn, being a mechanically enhanced super soldier, solving a murder mystery as a top notch quirky detective, meeting your dream date, or studying the blade – you know – that kind of thing.

At its finest, that’s what the metaverse promises: a place where you can be anything you want and do anything you want, no logistics required. Plug the jack in like Neo and say “I know kung fu.” and then *bam*, you do.

What the metaverse actually is so far is … hype. Meta has shown us Miis in virtual office spaces, investors are snapping up virtual real estate, VR / AR dev kits without killer content to speak of, and people have gone / are going (unclear which at any given moment) wild for NFT and crypto speculation on the promise of our imminent virtual world.

So many of these buzzy new ideas are built on pure supply-side logic, “once everyone is here, this’ll be worth something.” But how can we know when a metaverse concept actually creates value? By comparing them to the art form that’s made compelling digital worlds for years: video games.

Having obsessed over game design for more than a decade and practicing myself by creating a deck building card game, its tenets keep springing to mind as I see the “metaverse” hype parade pass by. And I continue to remember when I felt like a part of a kind of shared metaverse, the summer Niantic released Pokémon Go.

THE SUMMER OF POKEMON GO

I wanted Pokémon to be real so bad it hurt. I wished for them to be real every time I blew out my birthday candles from age five to age 15. I longed to travel the world as an elite trainer, befriending humongous, strong creatures who would fight by my side. Then maybe one day, I’d settle down with a family and be a gym leader. You know, the American dream.

And I thought that wish came true during the summer of 2016 when Pokémon Go came out. Suddenly I could hold my phone up to the world and see Pokémon wandering around beside me. I could tap on them, face them head on, and catch them (or not) with a swipe of my finger. I could duke it out with other players to become a gym leader and show off my team of hyper-powered eeveelutions.

The realization of this dream was so compelling that it propelled me out into the 100+ degree summer heat of Austin, Texas, loaded with sunscreen, water bottles, and spare battery packs for my phone. I wandered Auditorium Shores in search of Charmanders with co-workers, met strangers hunting for a wild Tauros outside the Texas State Capitol building, and almost dinged my car trying to catch a Seadra pulling into the Mueller HEB.

And the world came right along with me. Pokémon Go was downloaded more than 500 million times in 2016 and it was *everywhere*. Every small business wanted to be a PokéStop. And parents were debating the moral fibrousness of their kids somehow both a) being outside and b) having their faces glued to their phones at the same time.

Then it ended.

Pokémon Go’s user base dropped by 72% from 2016 to 2017. And I left too. Why? Because the game’s fantasy didn’t have the sense of progression to keep the world and me captivated.

DESIGNING GAMES TO BUILD LONGLASTING ENGAGEMENT

In my favorite definition of a game to date, Bernard Suits defines the playing of a game as "the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles."

In simpler terms, this means that games have to make you excited to overcome the challenges they present. It also implies a sense of game balance that makes players feel empowered, but not overpowered.

Ian Shreiber’s beautiful and sassy course, “Game Balance Concepts” outlines three key questions analyzing game balance as it interacts with player progression:

Is the difficulty level appropriate for the audience?

Does the game’s difficulty curve match the player’s skill growth curve?

Are rewards given out at a comparable rate to the rate of difficulty increase?

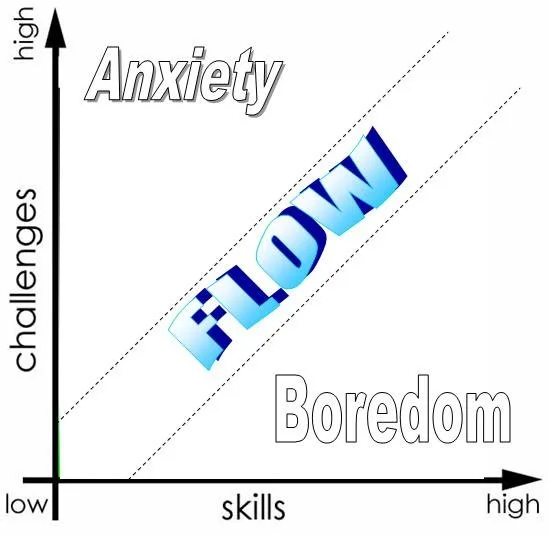

And all of these questions can and should be couched in a psychological concept called “Flow Theory.”

Chart based on Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi's Flow concept and research.

In principle, the theory is that people reach an ideal mental state when they take on a challenge that stretches their skills juuuuuuuust enough. You’ve likely experienced a flow state yourself while doing things like playing sports, playing an instrument, presenting a concept at work, or creating art.

“Real fun comes from challenges that are always at the margin of our ability. When balance is really perfect, people often zone out.” - Raph Koster, A Theory of Fun

And zoning out is what every game designer longs for players to do when building an experience. Flow is the holy grail of game design. And just like the holy grail, reaching it involves resolving your daddy issues with Sean Connery, fighting off bandits while racing through the desert, and choosing correctly when presented with a menagerie of goblets by an Arturian Knight (or at least it feels like that).

How do game designers do it? Loops.

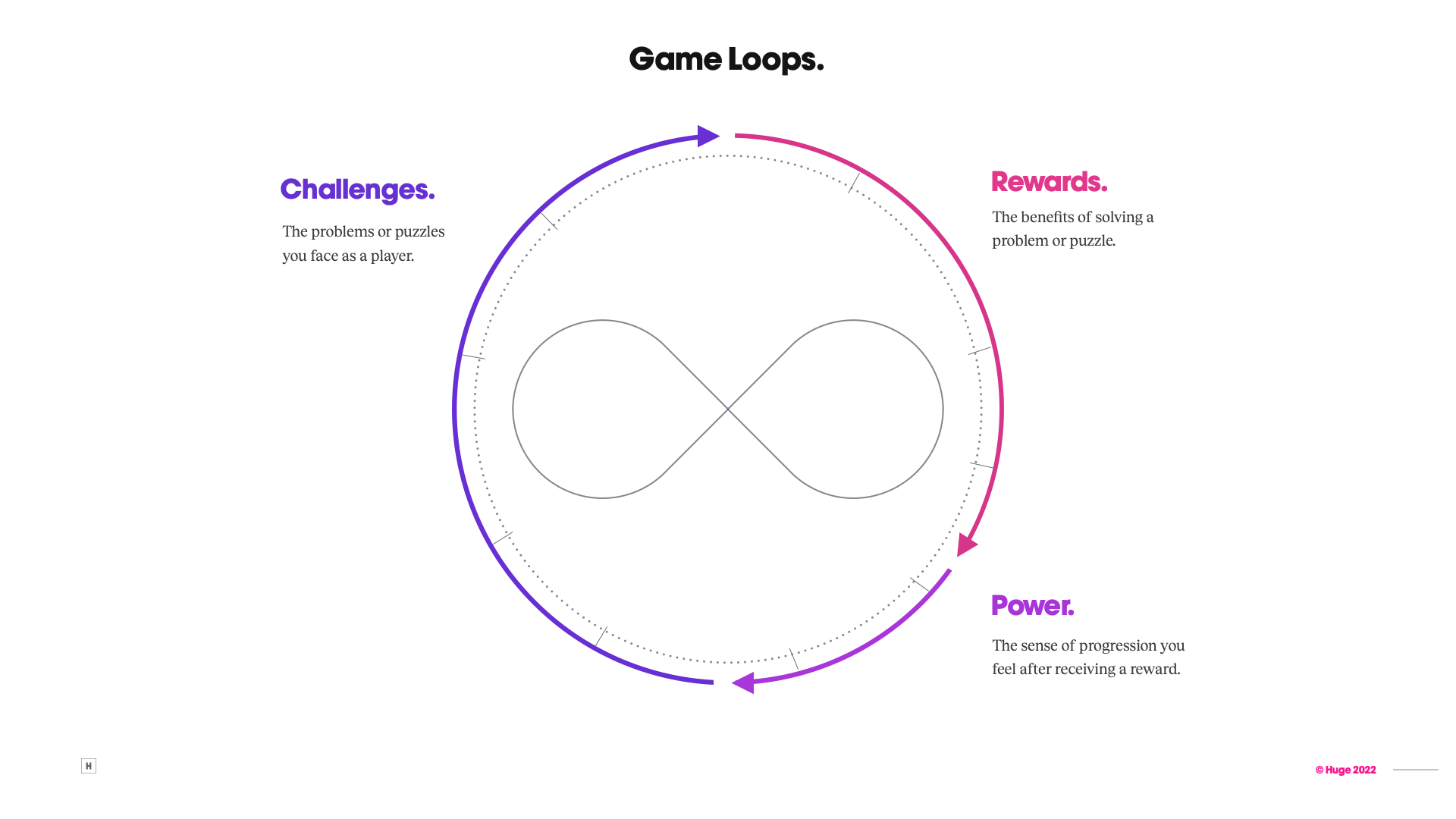

Almost every game system relies on a series of interactions that create a cycle for the player. We’re going to focus on positive feedback loops here, but negative feedback loops do exist, they’re just more commonly used to keep winners from winning too much rather than acting as a foundation of progression for a new player.

Positive feedback loops consist of:

Challenges - the problems or puzzles you face as a player.

Rewards - the benefits of solving a problem or puzzle.

Power - the sense of progression you feel upon receiving a reward.

After you gain power, you naturally want to test it. In Flow Theory terms, your skill level has increased, so you seek a new challenge at the periphery of those skills.

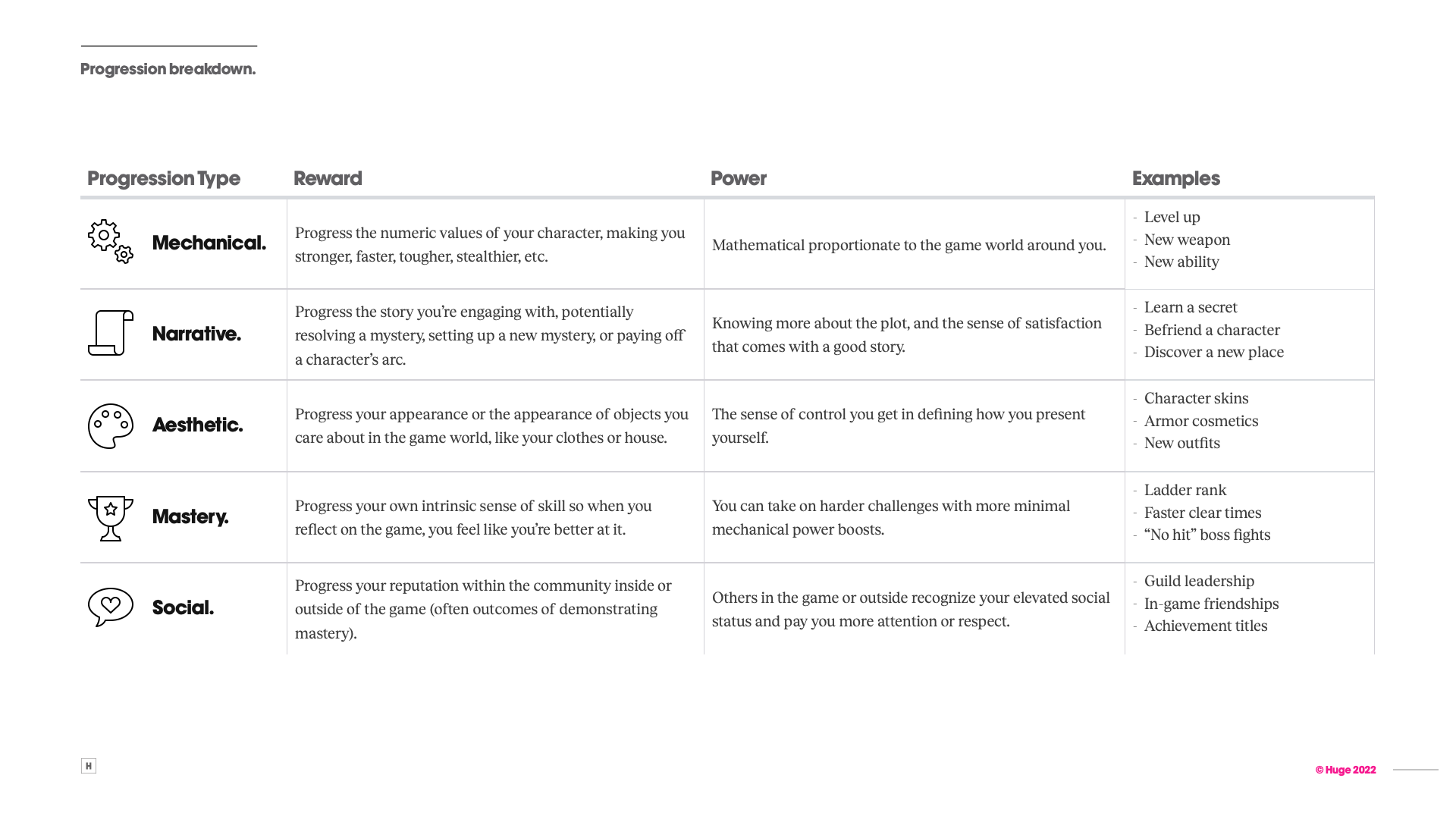

Rewards and Power can take a number of forms and they’re closely tied together to create a sense of progression:

Now we’re ready to talk about the loops in Pokémon Go, where it falls short, and what we can look for when evaluating new games and metaverse properties.

WHY POKEMON GO BURNED TOO BRIGHT AND TOO FAST.

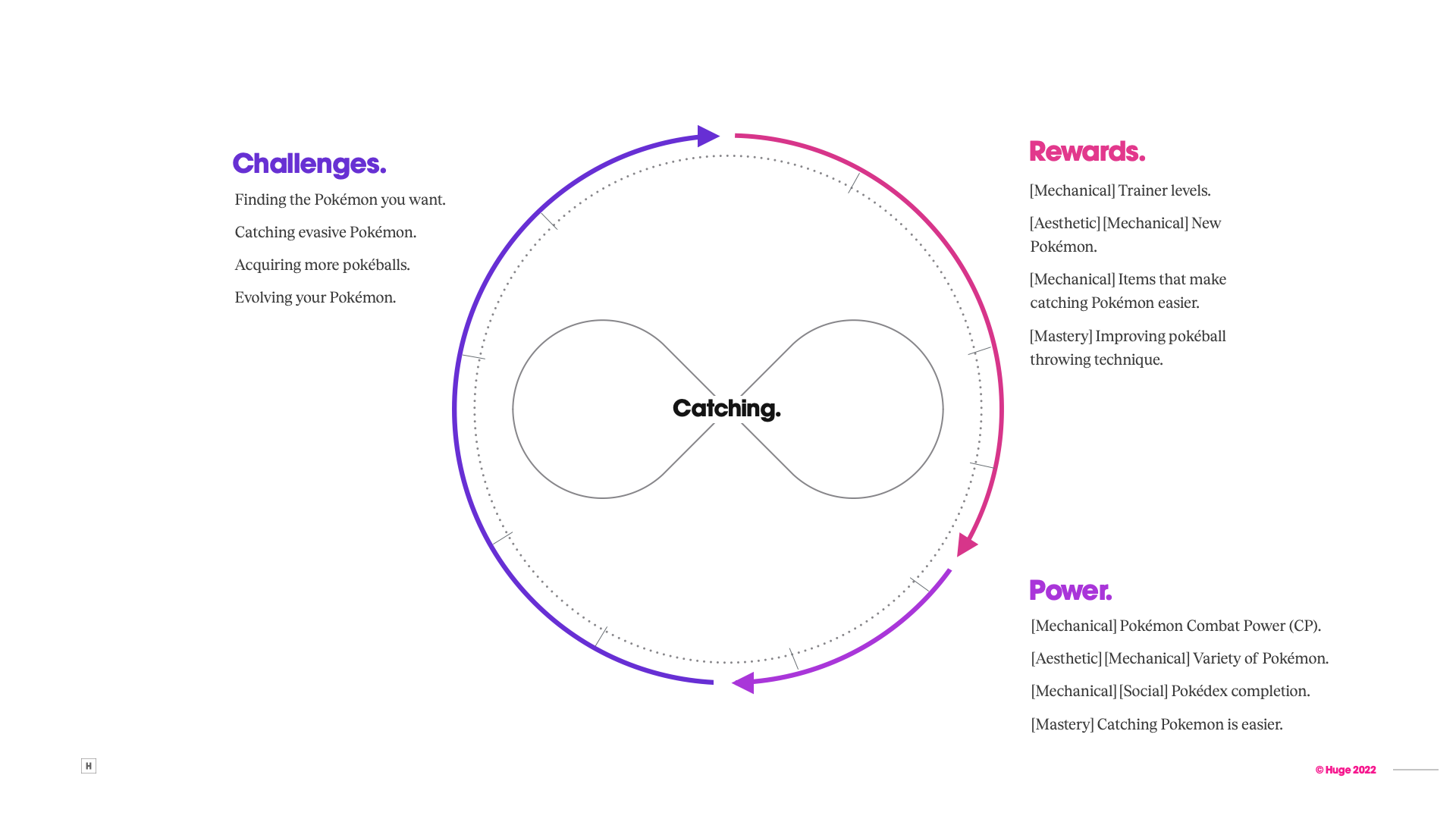

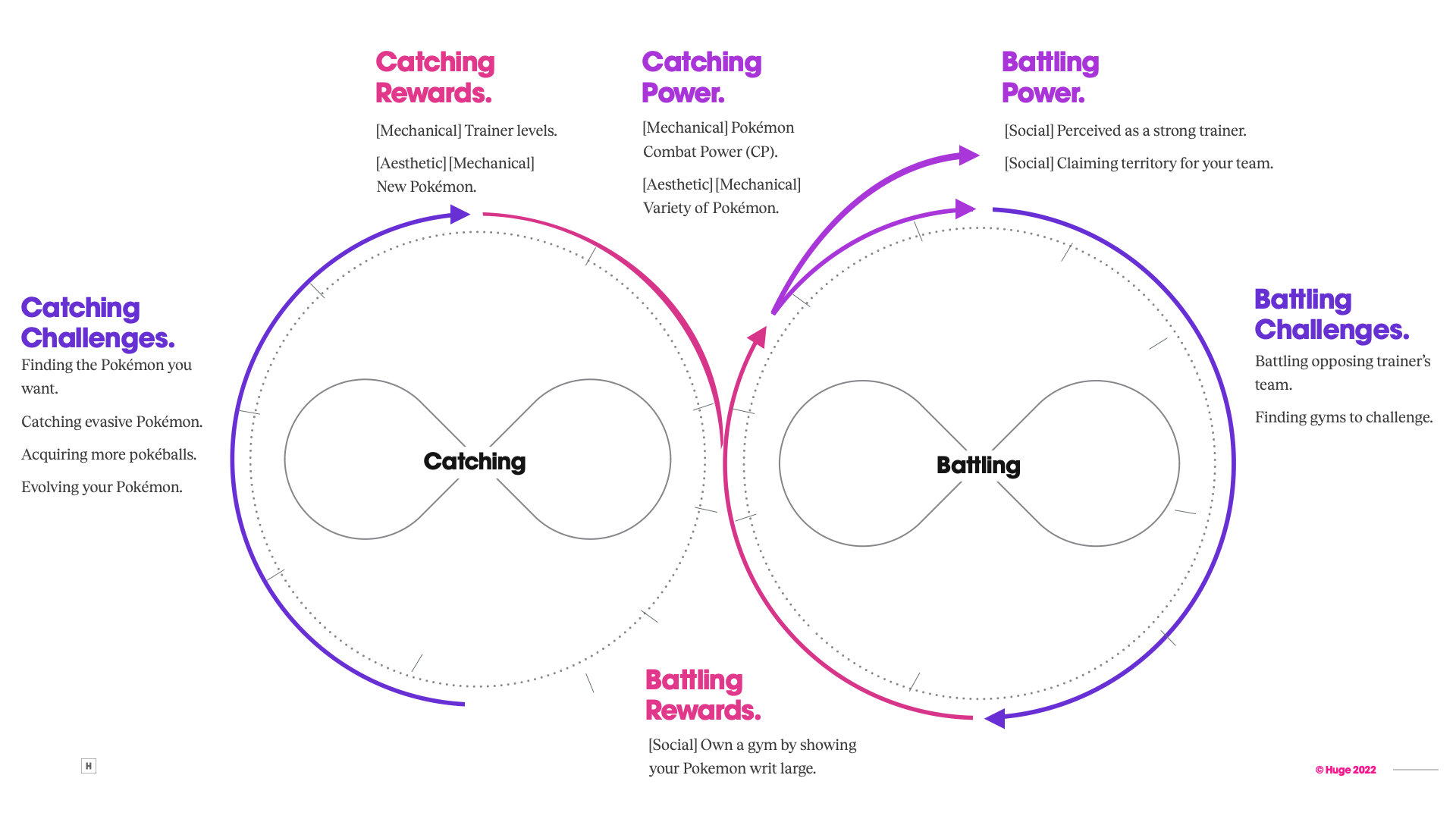

There were two primary loops in Pokémon Go when it came out in 2016, which link together to create the larger game system. The first is catching Pokémon and the second is battling Pokémon. You can only battle with Pokémon after you catch them, so naturally catching is an input to the battling loop.

An important note about the game to give up here is that from player creation, you choose one of three teams to align with, which adds social rewards / power when you make your team win.

*Disclaimer: Pokemon Go has evolved a lot since it came out in 2016, including more loops and 550 more Pokémon, but for our purposes, we’re sticking to an analysis of the original 1.0 release.

CATCHING POKEMON

BATTLING POKEMON

LOOP ANALYSIS

When we analyze the loops above, we can see that Pokémon Go is missing an entire category of rewards / power progression, Narrative. There’s no plot justification for the player’s role in the world and no mysteries to unravel.

The battle loop is also extremely underdeveloped compared to the catching loop. There are no mechanical rewards tied to taking over gyms for either your player character or your team beyond social perception.

And when we analyze both loops together, they don’t form a cohesive system. Catching Pokémon leads to a stronger battle team, but the battle team doesn’t help the player catch stronger Pokémon (unlike the main line Pokémon games where weakening a Pokémon is mechanically required to catch it). The rub here is that Trainer Level is the trigger stat for finding Pokémon with higher Combat Power, and Trainer Level is only elevated by catching new critters.

There’s another, more insidious problem hiding between the lines of loops above, and it has to do with difficulty. So let’s use our framework and revisit those questions from Ian:

Is the difficulty level appropriate for the audience?

Yes, at first the difficulty level is appropriate. It’s a mass market, free-to-play game.

Does the game’s difficulty curve match the player’s skill growth curve?

No, the game difficulty is consistent throughout the player’s time with the game when it comes to catching Pokémon and only spikes in PvP gym battles.

Are rewards given out at a comparable rate to the rate of difficulty increase?

No, rewards are given out at a consistent rate and there is no rate of difficulty increase created by the game environment itself, only other players.

While the broken macro loop certainly hurt Pokémon Go’s game system, the deeper reason for its player base’s enormous churn lies with its lack of difficulty, not necessarily its core loops. Specifically: the difficulty curve is entirely flat if you don’t want to fight over gyms. And why would you, if battling doesn’t give you meaningful rewards.

Both the catching and battle loops’ interaction patterns are easy to learn, but they’re also incredibly simple to master. As a player, you learn to throw “Excellent!” pokéballs, how to swipe on a PokeStop from exactly the right distance away, and develop twitch reflexes to tap on your Pokémon during battle. And that’s … all. The real difficulty within Pokémon Go comes from hard time cost, or as it’s commonly called in the gaming community, the grind.

Grinding - taking on the same rewarding, but easy challenges over and over again to gain the necessary power to overcome future challenges in the game.

Here are the rewards in Pokémon Go that are directly linked to the time a player sinks grinding:

Trainer level

Evolved Pokémon

Pokémon variety

Pokémon team strength

Gyms owned

Items that make catching Pokémon easier

And here are the rewards in Pokémon Go directly linked to player skill:

[this space intentionally left blank]

On release in 2016, Pokémon Go was an amazing, dreamlike experience, but it was optimized to take as much of your time as possible. And because its macro game loop is broken and its difficulty never increases, players only felt Flow State for a short time. Then, they hit the trough of boredom and moved on.

But can we determine if a new concept will have this kind of fad curve in the future?

EVALUATING NEW METAVERSE CONCEPTS, A QUIZ.

Metaverse enthusiasts are quick to pitch opportunities to audiences and brands, but to ensure that the concepts themselves are engaging enough to pay attention to, I'd recommend considering a few questions before investing your time or money:

Is there a way to either of these sensations for the target audience with this concept?

Inspire delight

Cultivate a flow state

What are the rewards and powers (of all types) for engaging in the activity?

Mechanical

Narrative

Aesthetic

Mastery

Social

Are the rewards and powers compelling for their audience?

What does the difficulty curve look and feel like?

Is the difficulty level appropriate for the audience?

Does the content’s difficulty curve match the player’s skill growth curve?

Are rewards given out at a comparable rate to the rate of difficulty increase?

What is the concept’s system designed to accomplish for itself and for its audience?

We’ll all face hard choices on what to bet on as new tech concepts emerge. There’s an aura of ground floor syndrome about the metaverse that’s tough to combat. But armed with a logical framework like the one above, both people and brands can validate if the pressure they feel to invest comes from hype or from an internal validation of their own experience.